| HOME |

Learning From the 2003

SHA Public Session’s

PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education Event:

What can be taken forward from this Public

Archaeology experience?

by Patrice L. Jeppson

Circulated for Comment

The PEIC K-12th Grade Issues subcommittee organized a public

education outreach event for the 2003 SHA conference in

(1) the proposed goals for the event (the outcomes hoped for)

(2) the objectives designed to accomplish these goals (the strategies

prioritized so

that desired outcomes might be reached)

and

(3) the results of the conducted event (an evaluation of the goals

reached and/or

missed including the variables impacting the objectives–both

those within

and those beyond our control).

These aspects of the PEIC

K-12 Social Studies Education Event represent some of the questions that count in this and in any

public archaeology endeavor. At least some of what was learned from this experience

can and should be taken forward to future SHA PEIC outreach endeavors and

may be of use in planning public archaeology undertakings in general.

The Research Context of

the PEIC K-12 Outreach Event

Public Archaeology is a rapidly evolving area of practice

within the field of anthropological archaeology and is now regularly found

as part of disciplinary practice comprising archaeological conference and

session themes[2],

publication topics[3]

as well as agency[4],

non-profit[5],

and professional Society agendas[6].

The pursuit allows the profession to proselytize about archaeology’s needs

by presenting to the public the insights gained while serving as keepers of

the public trust with the aim of ensuring continuing public support for archaeology

and enlisting public cooperation in efforts to protect archaeology sites from

looting, vandalism, and economic development (For discussion, see, among others

Hersher and McManamon

2000). Beyond public archaeology directed through this disciplinary lens,

there is also a public interest area of practice whereby, in acting civically

beyond our disciplinary goals, archaeologists seek to integrate intellectual

practice with the daily lives of people giving the public information they

need and can use so as to improve communities through archaeology while improving

archaeology through communities.[7]

Public Archaeology is found prominently featured in the

recently revised Society for American

Archaeology Ethics guidelines where it bears fundamentally on the central

guiding ethical principle of Stewardship (SAA Principle of Archaeological

Ethics No. 1).[8]

The topic also directly constitutes another SAA Principle of Archaeological

Ethics, No. 4 (out of 8): Public Education and Outreach.[9]

Public Archaeology is likewise a feature, albeit one positioned less centrally,

in the Society for Historical Archaeology’s

Ethical Principles and Professional Guidelines for Practice forming Principle

7 (of 7) and Guideline 7 (of 7).[10]

While increasingly recognized as important and ever more

present as a form of practice, public archaeology is nonetheless still finding

its footing (Downum and Price 1999; Gibb 2001).

Applied anthropologist Erve Chambers has recently

summarized the current state of public archaeology as an applied form of practice

and found it lacking in critical evaluation (Chambers, forthcoming[11]).

Chambers writes:

…it is worth asking how

much we actually know about the extent to which such [applied archaeology]

activities do contribute to public education. I mean this in two ways. First,

is the message getting across in general? How, for example do people actually

read heritage into a site, and what is the relationship between their readings

of heritage and the intentions of archaeologists? Second, is the message getting

across in specific cases? How effective, for example, is a particular educational

strategy, or how well do different kinds of sites fulfill their educational

and outreach missions? Much is assumed in terms of the educational mission

of public archaeology, but I think we know very little in this regard. In

my admittedly limited experience, it appears that the evaluation of archaeological

public education activities is often limited (if it occurs at all) to relatively

simple surveys designed to collect visitor demographics and gauge first impressions

related to site specifics and the valuation of archaeological inquiry. That

such evaluative efforts are often associated with attempts to justify or seek

additional support for archaeological work makes their scientific usefulness

suspect….

….There is as yet no standard,

or even clear means, for placing such case material within the context of

similar efforts. What I mean by this should be apparent if we think of the

way we typically write basic (i.e., nonapplied) research. It would be difficult to get any such

material past an editor or peer reviewer without

providing a fairly comprehensive review of how the research fits within the

context of earlier inquiries.

These comments highlight

the ill-defined nature of evaluation in public outreach practice identifying

two critical failures to this end. The first is the need to determine whether

‘the message’ in a public archaeology effort gets across. In other words,

is what the archaeologist hopes to convey ‘conveyed’. The second is the need

for adequate evaluation strategies. There needs to be critical reasoning behind

any ‘effectiveness/success’ assessments done on outreach endeavors. The fact

that evaluation in public archaeology practice is lacking is increasingly

being recognized by many publicly directed-archaeologists and there are individuals

working to establish useful criteria for the formal assessment of public outreach.[12]

To be fair, it should be pointed out that the course of public archaeology

endeavors and the subsequent state of their follow-up evaluation are simply

following the evolution of activity as pursued in general archaeology practice:

One doesn’t interpret a site before it is excavated nor does one conclude

about regional patterns before multiple sites are investigated. Many would

reasonably state that evaluation in public archaeology can only take place

after there are significant efforts that can be analyzed and compared. Given

the varied outreach efforts undertaken (during the past two decades in particular),

and the body of valuable information gathered to date, it is time that public

archaeology address evaluation as a part of all endeavors. Having said this,

it should also be noted however that another view holds that evaluation is

expected and built into modern projects in most other professional fields

(education, business, etc.) and that publicly-directed archaeologists have

been remiss in their undertakings for not beginning with this as a feature

of their efforts.

The 2002 PEIC K-12 Social

Studies Education Event was designed from the beginning with the need for

evaluation in mind. To this end, a formal proposal was constructed at the

outset outlining the desired goals hoped for and with objectives put forth

as to how these goals might be met (Jeppson 2002b) This was done in the hope

that by formalizing the nature of the undertaking the effort would lend itself

as useful research that could be objectively learned from.

The Proposed 2002 PEIC

K-12 Social Studies Education Event:

In early 2002, Tara Tetrault and Patrice

L. Jeppson – the PEIC K-12th Grade Issues subcommittee – decided

to arrange an event for local

Designing Effective Outreach

The PEIC had gained substantial information about how to effectively

reach out to the public school teacher during the educator/archaeologist panel

discussion organized for the 2002 SHA meeting in Mobile, Alabama (a PEIC and

ISRC sponsored event).[13]

I also had gathered information about how to undertake such outreach from

the History/Social Studies Consultant for the Los Angeles County Office of

Education who presented at SHA in

Specifically, these sources suggested contacting/targeting teachers

for archaeology outreach using ‘institutional networks in place as part of

the culture of schools’. This directed strategy included targeting school

district social studies curriculum specialists/directors (as opposed to the

common practice of archaeologists contacting school principles), providing

a letter from the National Council for the Social Studies endorsing the event

(utilizing the NCSS liaison to SHA), and scheduling teacher events on weekends

rather than weekdays (because securing leave just after the Christmas Holiday

is unlikely and inconvenient for teachers and is ever more unlikely due to

the lack of funding for substitutes)[16].

This was information gathered for inclusion in the SHA Annual Conference Public Outreach Session

Guidelines and Conference Organizer Overview[17].

It also informed the teacher targeting strategy for the 2003 PEIC Social Studies

Education outreach event.

Meeting Educator’s Needs

Experience gained from the audience discussion during last year’s Panel

Discussion also identified/verified that there are at least two audiences

of publicly-directed archaeologists found within the SHA membership: one more

novice and one more experienced with working with schools. This division in

experience parallels to a degree the two different approaches found in formal

school outreach - one of these being extra-curricular (offerings outside the

normal course of study offered) and one being curricular-based (where archaeology

content is tailored to meet pedagogical concerns). While either extra-curricular

or curricular efforts may be designed towards meeting civic needs, both types

of outreach as they are practiced primarily tend to be motivated by ‘insider’

disciplinary needs related to Stewardship. Thus, whether it is a matter of

inexperience or motive, the end result in much public outreach to the formal

school sector is that all to often the archaeologist provides the educator

with resources that are either less relevant or less usable for teacher needs (e.g., not

in line with education’s needs). The 2003 PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education

Event was therefore also designed as a way to help historical

archaeologists better understand the needs of educators. It was hoped

that the educational aspects of the event would offer the membership insight

into how archaeology is used in the classroom by educators for education purposes

(as opposed to for archaeology needs).

These two aspects of public

outreach informed the goals for the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education Event

which were:

(1) effectively

contacting an audience of teachers

and

(2)

targeting the publicly-directed SHA membership with

information about education needs as opposed to archaeology needs

Drawing on information gained from (the above mentioned) education

and education-connected sources, several objectives were designed and formally

proposed to help meet these two desired goals. These objectives centered on

the PEIC Event planning taking two actions:

(a) creating a joint teacher/membership

format for the event

and

(b) implementing specific

scheduling tactics sensitive to audience needs

These objectives in turn

drew on the budding NCSS/SHA affiliation begun by Tara Tetrault (the SHA Delegate to NCSS) as part of her Inter-Society

Relations Committee duties as well as from the relationship SHA established

with NCSS in 2002 during the Panel Discussion (where the NCSS President and

an NCSS Board Member were participants).

The resulting event proposal forwarded in mid-year to the Chair of

the PEIC and to Allen Leveled, the local host public session organizer, follows

here:

Proposed 2002 PEIC Event

The PEIC K-12 subcommittee (with the assistance

of the National Council for the Social

Studies*), hopes to organize

a teacher-archaeology discussion event at the SHA’s conference in

ABSTRACT:

"How Is Archaeology Used In the Classroom?

An archaeologist and two educators will

work in tandem in this session, sharing their professional expertise with

an audience comprised of both archaeologists and teachers. First, a Current

Research presentation will be made by an historical archaeologist. This archaeology

presentation will then be deconstructed/translated by Social Studies Curriculum Specialists

for use in the classroom. In this way, local

Rationale:

Both educators and archaeologists will

benefit from this event:

-Educators will receive formal instruction

on how to incorporate archaeology content into lesson plans. (The teachers

will thus be primed to make the most of the Public Session’s offerings). This

event helps meet the Society’s public outreach objectives.

-Observing how educators make use of archaeology

for education needs will be informative (possibly eye opening) for the Society’s

membership. This event will help prepare the membership for stewardship activities

in outreach to the formal school sector.

Based on the membership’s attendance at

last year’s PEIC panel discussion of educators and archaeologists, it is apparent

that SHA has an audience for this topic.

*The NCSS is the largest association in the

nation devoted solely to social studies education. Their 26,000 members are

comprised of K-12th grade classroom teachers, college and university faculty,

publishers, and leaders in the various disciplines that constitute the Social

Studies. NCSS works to strengthen

the social studies profession and social studies programs in schools through

professional development, resource provisioning, and legislative network activities.

NCSS is particularly important

to SHA, and to archaeology in general, because NCSS

standards guide social studies decision-makers in K-12 schools. This influence

extends to teachers who are not NCSS

members (and it is estimated that approximately 200,000

Mechanics

.

The event would

ideally be an hour-long session with 20 minutes for an archaeology presentation

followed by 40 minutes of commentary by the education discussants.

.

This event

would be advertised to both the membership and to an invited public of social

studies educators.

.

The NCSS’ Delegate

to SHA will be part of this event.

.

This session

will expand on issues identified during the Archaeologist-Educator

Panel Discussion held last year at SHA in

Participants

The educators to be tapped for this event*

include:

Dr. Susie Burroughs, Assistant Professor, Department of Curriculum

and Instruction, Mississippi State University’s College of Education, Member,

NCSS Board of Directors, and NCSS Delegate to SHA.

George Brauer, Social Studies Curriculum Specialist

and Director, Center for Archaeology, Baltimore County Public Schools. (Past

Recipient of the SAA award for Excellence in Public Education).

Dr. Burroughs instructs new teachers in

general Social Studies Curriculum and Instruction strategies. She will bring

to the table classic as well as cutting edge pedagogy. George Brauer on the other hand is one of the few Social Studies

Curriculum Specialists on the ground (in the classroom, and at a District

level) whose job it is to actually implement substantive archaeology research

into K-12 curriculum. (He won the NCSS' own 'Outstanding Curriculum in the

nation Award' for doing just this.) He will offer the teachers and the archaeologists

in the audience his expertise and experiences with integrating archaeology

detail into classroom-based, as well district level, curriculums.

Dr. Burroughs and Mr. Brauer are both part of a group of education specialists working

with the PEIC to improve public archaeology outreach to the formal school

education sphere.

*The NCSS will not be in a position to confirm

the names or number of participants until later in the year. It is possible

that the NCSS President will attend

as well (as happened last year).

The Archaeologist tapped for the event:

Selection of an archaeologist for the initial

Current Research presentation has not been finalized. Anyone with interesting

data will do, although we are sensitive to the fact that many of our colleagues

are insensitive when dealing with the public and we wish to have someone experienced

and interested in public archaeology outreach. Tara Tetrault and I have decided not to step in for the Current

Research presentation (although one of us can do so if needed). We know there

are others doing exciting public related work and we don’t want to monopolize

a PEIC event. Diana Wall is willing to do it but she is heavily committed

during the conference and also has suggested that a local researcher might

be better.

It is true that the teachers who attend

this event could follow through with the featured archaeologist, using him/her

as a local resource (for site tours, school visits, and contact assistance).

If so, the PEIC would be pleased if this event contributed

to the local archaeology in this way.

Inviting the Teachers:

.

The NCSS' (as

they are part of this) would assist us in advertising the event. The NCSS

has offered to make available for us an official letter of support that will

put their stamp of approval on the event as an educational undertaking for

professional Social Studies teachers. This official stamp of approval by a

major professional education society will be helpful in attracting social

studies teachers and curriculum specialists to the conference. The pull of

this educational skills offering combined with a public session that offers

enriching ‘content’, should be quite a draw.

Specifically, this advertising would amount

to contacting social studies specialists in the local districts, social studies

network teachers, and local college teaching departments of curriculum and

instruction.

.

We realize

[the local host] has responsibilities for the entire public beyond just social

studies teachers (and beyond teachers in general). We would like to offer

our assistance for the general session planning with whatever teacher contacts

and support we can, in turn, provide.

Scheduling

Scheduling of the PEIC event should take into account the following

practical needs and unique circumstances:

.

Scheduling the event early

on the day of the public session would allow the teachers to take the best

possible advantage of what the Public Session has to offer: The education

event will provide the teacher with the skills needed to incorporate that

which the Society offers in the Public Session.

.

Early scheduling

would also mean that the 'family' problem encountered in past teacher-directed

conference offerings would be minimized. The teacher's families could be expected

to sit through the education event if it was scheduled earlier in the day.

This is a plausible (i.e., not unreasonable assumption) because the kids would

know that ‘cool slides’ -- or hands-on activities, or whatever else you have

planned -- would soon start again (in the Public Session).

.

The NCSS (both

last year in Mobile and the year before in Long Beach), as well as a Teacher

Group that advises the PEIC, have suggested to SHA that teacher-directed events

be planned with an eye towards the fact that teachers will have kids and spouses

in tow. (We wouldn’t want to appear to go against the NCSS’ specific (and

sought for) professional recommendations for scheduling of a teacher event

-- especially when they are endorsing our event to their professional membership

of teachers.)

.

Effective teacher

instruction will be hampered if the kids in tow became disruptive which would

likely result if the event were held after the Public Session. It is unrealistic

to expect kids to sit patiently through an event that is not geared towards

them that is held at the end of the day when they are also tired and hungry.

.

The membership

would less likely stay around to attend the event if it were held at the end

of the public session. It would be long after all the other professional conference

doings are completed. A unique opportunity for members of the Society to learn

first-hand about how archaeology is used in schools would be missed.

.

Archaeologists

are in the process of working with the NCSS to put together a joint body

of professionals (archaeologists and educators) that will work on archaeology

standards for a national social studies curriculum. An impressive show of

what archaeology can do for education would be professionally desirable

specifically because the NCSS are on board. A later time slot, with fewer

audience participants (for the above stated reasons), would make for a less

impressive showing.

(06/2002)

________________________________

Implementing

the Social Studies Education Event Planning:

As

the second half of 2002 unfolded and the PEIC K-12 event’s implementation

began, two significant modifications had to be made to the above proposed

event design. Both of these changes

resulted in relevant learning experiences - one

of which is already incorporated for future PEIC (and public archaeology)

needs. The first change resulted when a major problem developed with the

National Council for the Social Studies’ participation in the PEIC event.

The second developed when the other Social Studies Education Specialist, George

Brauer, became unavailable. These changes and the

resulting modifications are described below.

NCSS Related Changes and Results

While the Past NCSS President Adrian Davis had appointed a liaison

to SHA and was very inspired about future joint efforts between social studies

and archaeology, our experience this year taught us that it seems likely that

bridge building between the archaeology and education professions will likely

grow in fits and starts with some NCSS presidents more on board than others.

The new President of NCSS stated to Tara Tetrault

that financial concerns for (this very large and financially flush - in comparison

to SHA) professional body were a problem this year. Negotiations were then

likely dealt a fatal blow by paralleling archaeology interests: NCSS was also

approached with invitations for participating in an ISRC-sponsored WAC session

and for a Project Archaeology curriculum

writing workshop.[18]

Both of these other archaeology invitations represented local events for the

NCSS (local to the National NCSS headquarters in

a) National NCSS directed

Tara Tetrault instead to a

This contact had significant

results for the PEIC event. The RISSA President (a private high school History

teacher and Chair of the school’s Social Studies Department, and State History

Day Co-Organizer for

This membership list offer proved fortuitous because the

teacher targeting strategy was facing problems. I had learned as I attempted

to implement the outreach target strategy (using institutional Social Studies

networks) that (a) RI had no state social studies standards, (b) that there

is no Social Studies curriculum specialist at the state office of Education

(a vacant position), that (c) the state of Rhode Island prides itself on independent

school district autonomy and, unlike most other places, is not subject to

the state's control --so therefore there was no set curriculum at a uniform

district level to tap into and in many cases each teacher is doing their own

thing. All this meant that using the recommended institutionalized social

studies network was impossible in the

All we could do was 'not go the institutional route' (which

is what NCSS et. al, and my own experience suggested --and which was what

was proposed to test) and go instead the individual teacher route (contacting

teachers one by one). This was not the preferred way to do things but was

still a tactic that could be explore/tested. In fact it was what the one classroom

teacher (Sara Wade) as well as one of the two NCSS panel participants last

year (the Board member) said we should also try to do: both routes – pursue

the individual teacher and the institutional route when we could.

b)

As

a result of the SHA PEIC /WAC/Project Archaeology ‘confluence of invitations

to NCSS’, the PEIC K-12th Grade Subcommittee initiated a program of outreach

updates to agencies, non-profits, and professional archaeological societies

informing them of (a) the potential problem of uncoordinated public archaeology

outreach to the education profession and (b) towards that end, began providing

these colleagues with information about what the SHA PEIC K-12 has been up

to (Jeppson

2002c). These measures were taken in an effort to encourage coordination of

strategies that target the audience of educational professionals, namely the

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), but this co-ordination should

have broader benefits.

The objective of this action is merely to increase information sharing

among education-directed archaeologists but one result may be that individual

outreach activities will prioritize audiences. As there are so many archaeologists

active in public outreach to the formal school sector these days, and as this

outreach regularly involves targeting the same education groups, it seems

it would behoove us all to make an effort to keep one another informed about

our activities - if only so that the profession comes across as organized

and informed. Archaeologists in the societies, agencies, and non-profits tasked

with outreach to the formal school sector will one day soon need to think

about collaborating, coordinating, and possibly prioritizing so that short

term projects don't divert attention from long term possibilities. This is

especially true on the road to developing national archaeology standards for

Social Studies Education through creation of an educator/archaeologist-based

'Archaeology Alliance' (along the lines of what the geographers have done

with the Geographical Alliance or the economics professionals with the National

Council on Economic History). The time is approaching where all of us need

to be part of an on going conversation about short and long term goals for

working with NCSS and coordinating our efforts even if we have somewhat separate

agendas.

To date, this outreach update program includes indexing

PEIC K-12 activities on the SAA operated Archaeology and Public Education electronic

newsletter (A&PE) and emailed updates to the SAA’s Manager of Information and Public Education and to the

Director of National Project Archaeology. There is an effort in progress to

present an ‘update’ during the SAA Public Education Committee’s (PEC) annual

meeting and email correspondence with the AAA’s Public Education Initiative project staff

will be soon be enacted. Public Archaeology in general can only benefit to

this end.

Other Format Changes

A second modification to the proposal occurred after the educator George

Brauer gave notification that he was unable to attend

SHA. This change too, in the end, led to a research conclusion (explained

below). A social studies specialist and 32-year, avocational archaeologist with extensive historical archaeology

experience, it was George Brauer who had originally

proposed to me in 2001 the idea of a deconstruction/‘translation’ education

event for archaeologists at SHA. I had collaborated with George Brauer at the Center for Archaeology/Baltimore County Public

Schools from 1998-2002, and he mentored me extensively about what archaeology

needs to do to effectively coordinate with social studies educators for social

studies education needs. When the plan for his participation in the PEIC event

was disrupted, George felt that my years with him meant I could do well enough

in an educator’s absence. While I had experience with curriculum and instruction

in collaboration – and Tara Tetrault too had experience

with writing curriculum - I was extremely reluctant to go ahead with the PEIC

event without an educator on board because (a) teachers don’t like non-teachers

to tell them what or how to teach and (b) I felt that archaeologists needed

to see what teachers do -- not be told about what teachers needed by

another archaeologist.

As primary organizer, and because I felt strongly that the deconstruction/

translation portion of the PEIC event should not be directed by an archaeologist,

alternatives were sought to replace George. However, as the RISSA President

had coincidently at this time declined to participate as part of the presented

program (replacing the NCSS national representative), and because time was

running short, I made the decision to reformat this segment of the program

in a manner that would allow for, and hopefully encourage, the audience of teachers to share their ideas

about the presented archaeology with one other and with the archaeologists

in attendance. This way, the teachers would still come away with ideas

about how they could use the presented archaeology in the classroom and the

archaeologists would still have an opportunity to see first-hand how educators

use archaeology for education needs.

Two other factors were in mind when making this substitution. First,

not all teachers desire or are capable of constructing

curriculum themselves -- and this could especially be so given archaeology

content is something teachers are unfamiliar with. This factor meant that

the substitution of an audience discussion might not be an effective plan.

So another measure was put in place. We already planned to have a classroom-ready

lesson plan to distribute as a take away handout. This lesson plan would be

moved ‘up front as presented commentary’ to serve as a means to encourage

the discussion we desired if discussion proved lacking. Teachers could respond

to this lesson plan with ideas of their own and this might, in turn generate

further discussion. Moreover, this lesson plan could also serve as THE education

segment’s contribution in case the teachers were reluctant to speak up in

another profession’s forum (and be observed by these others).

Fortunately, when he abdicated, George Brauer

made the offer to help us in any way possible including advising us on a lesson

plan that could be used by us in his place. This would be a lesson demonstrating

how the archaeology presented in the first segment of the event could be used

in the classroom – essentially everything originally planned minus an educator

actually demonstrating/discussing it. At the same time, this would be something

(an educational resource) designed by an educator so it would not face rejection

by the educators. (It wouldn’t be an archaeologist telling an educator how

and what to teach.)

To this end, George Brauer designed for our

use a lesson plan modeling how to use archaeology and history in the classroom

to study social studies topics. He used

As part of the revised event proposal, this lesson plan would be modeled

IF the educators did not immediately take up discussion on their own at the

end of the archaeology presentation. If the lesson model were needed (because

the teachers didn’t ‘discuss), it would, ideally, generate discussion among

the educators in the audience. Tara and I would loosely direct any resulting

‘discussion’ (namely keeping the discussion on track, allowing archaeologists

to ask questions and share education-related experience but preserving the

time for educators to discuss how archaeology could be used in the classroom).

Thus, even with the necessary substitutions, the teachers would have access

to current research and be able to take away with them how to use the archaeology

presented during the event in the classroom. The archaeologists meanwhile

would still see how educators could use archaeology in the classroom for educational

as opposed to archaeological needs. While some objectives for accomplishing

the stated goals were modified, the original goals remained viable.

The Archaeology Component of the Event

As format modifications were integrated, and the event planning moved

forward, the co-organizers also spent previewing current research presentations

at historical archaeology conferences in an effort to identify a talk that

would be useful for the Social Studies Education event. A talk by David Orr

was selected and he was approached about reprising his CONEHA presentation

during the public session at SHA (Orr 2002).

This presentation was selected because it touched upon several topics

covered in middle school and high school in Rhode Island (U.S. Presidents,

Historical Landscapes, Revolutionary War, US History, Life in Colonial America,

How people view themselves overtime, how people created and changed structures

of power, authority and governance, Revolution and the New Nation etc.,).

The information in the talk could also be applied more generally by innovative

teachers for other curriculum needs -- for example, for Civics (e.g., students

could write the President or Head of the National Park Service about the need

to restore

Orr’s talk also compared new archaeology data from recent excavations

to what was written at in period documents. So the talk provided useful content

for teachers who want to instruct about the strengths and weaknesses of primary

documents and to compare primary and secondary documents. It was hypothesized

that we could in fact introduce the education segment of the event with an

overture to the educators saying something about how archaeologists perceive

this content as an opportunity to teach about primary documents by using the

learning skills of gathering information, forming hypotheses, and re-evaluating

(by breaking the class into two groups, giving the different groups the different

data sets, having them draw conclusions independently, then redrawing conclusions

once they hear the other groups information). The educators, in turn, could

correct or corroborate our assumption leading the education segment discussion

to take off from there.

Orr's research comparing the archaeology and documentary record was

moreover a good example of historical archaeology. His research would not

just verify with archaeology what the documents say or vise-versa but instead

used the two data sources against one another to extend what is known about

the past beyond that possible using either resource in isolation. Importantly,

Dave Orr is also a terrific presenter when he speaks. The

Rounding out the archaeology portion of the program would be handouts

for the teachers to support this talk. These would include professional archaeology

society material as well as handouts made specifically for the PEIC K-12 Social

Studies Education event. The former could be used as a classroom resource

(for example for Career Day) and the latter could be used as ‘prompt notes’

that the teacher could draw on when discussing the Orr talk topic with the

class. One handout would be useful for a student reading as well. The materials

gathered for dispersal included the SHA brochures “Careers in Historical Archaeology”

and “Underwater Archaeology”, the SAA brochures “The Path to Becoming an Archaeologist”

and “Experience Archaeology” and an SAA handout entitled, “Educational Materials

Available from the Society for American Archaeology Public Education Committee.

Handouts produced for the event included an archaeological education fact

sheet entitled “Archaeology as Education: Some Identified Benefits” (for Students,

Teachers, and for Archaeology), and a general archaeology fact sheet containing

the kinds of knowledge archaeologists rely on when they conduct archaeological

research, a short list of important archaeological sites and finds, types

of Historical Archaeology Sites, a small sample of historical archaeology

sites, a list of reasons that people visit archaeology sites, a list of what

archaeology contributes to (economy, tourism, heritage, etc.), and a list

of Valley Forge Web Resources directly linked to the David Orr talk and research.

An NPS web resource download “Discovering What Washington’s Troops Left Behind

at Valley Forge”, photocopied for the event would serve as the suggested Student

Reading and as an ‘Orr talk - High Points Fact Sheet’ while a Valley Forge

map download, “Valley Forge Encampment” would be a useful student resource

sheet (<www.cr.nps.gov/logcabin/htm>). A Social Studies Education

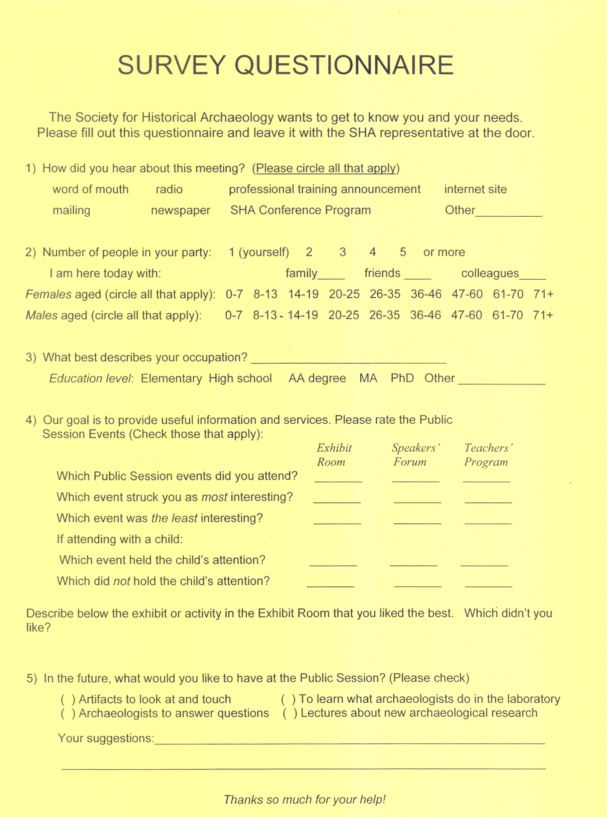

Event Survey Questionnaire seeking feedback on the educational aspects of

this event would also be a handout.

Pencils with archaeology as education embossed slogan were also designed

as a give-away to go along with these handouts (courtesy of myself and Tara

Tetrault). In preparation for this item, several

slogans were run by the PEIC K-12 Teacher Help Group and by a handful of publicly-directed

archaeologists. The archaeologists and teachers came down united on different

slogan directions. The teachers selected slogans about archaeology (“Archaeology

- Dig Into The Past!”, “Archaeology – Dig It!”) while the archaeologists chose

education sounding slogans, (“Teach Archaeology”, “Teach With Archaeology”,

“Teach The Past”). When queried about each others choices, the teachers responded

that the education directed slogans looked like “You are telling us what to

do” or “makes us feel bad because we don’t know enough about archaeology”.

The archaeologists expressed preservation concerns in that the archaeology

slogan, to them - or if not to them, to other archaeologists (!) - could be

seen to be promoting excavation by lay people. My own experience indicated

that this is a misguided archaeology mindset - that archaeologists do not

understand teaching objectives and that this kind of fear is not valid (Jeppson

and Brauer 2003).

This completed the planning

for the proposed plan that formed the basis of the PEIC K-12 contribution

to the SHA Public Session held on January 19th:

______________________________________________________

SOCIAL STUDIES LECTURE/DISCUSSION:

(

- Revolutionary War Archaeology for Social Studies Educators

-

** 'Cabins and Command:

George

Washington and the Hutting of the Continental Army at

A

talk to be presented by David G. Orr, National Park Service Archaeologist

and

Research Professor of Anthropology,

***

'How Can This Archaeology be Used in the classroom?':

An Audience Participation Discussion

Educators will explore this topic sharing their professional expertise

with one another and with a group of education-oriented

archaeologists

(teaching them about the kinds of resources

educators want and need!).

____________________________________________________________

This plan was not designed as a typical teacher workshop where teachers

would break into small groups to learn or operationalize a curricular lesson plan. That type of event

was untenable because a broad range of social studies teachers were invited,

we had no idea of who or how many would show up, and no way of knowing in

advance what grades or social studies topics (courses) would be represented

among the teachers in the audience.

In regards to the ‘teacher targeting strategy’, all high school

teachers on the RISSA membership list were contacted via a flier, by name

(with their printed name followed by “RISSA”). Those on the RISSA list with

email addresses were contacted

by email, as were high school teachers at RI schools with internet Email addresses

archived. There were 41 successful (not bounced) emails sent out although

we have no way of knowing how many of these were read. A total of 120 fliers

were mailed in bulk to Social Studies departments at 28 schools. These fliers

(sent in batches of between 4 and 8, depending on the number of social studies

teachers in the department) were directed to the teachers by name (about half

of these teachers were also on the RISSA list.) The envelope carried the name

of all known Social Studies teachers. A note was attached to the top flier

asking the named Department Chair to pass on the enclosed fliers. This bulk

mailing strategy was chosen to limit mailing costs.

An email notice about the event was posted on three RI teacher chatboards, and emails notices were sent and fliers mailed

to two curriculum resources centers located at two local colleges. Two professors

of Social Studies and Secondary Education were also sent emails and fliers

and were asking to share the information about the event with their students

- teachers in training - that they thought would be interested. Email notices

were sent to the leadership of the RI National Education Association (a union),

the Director of the RI Association for Curriculum and Instruction, and all

the board members of the RISSA. Letters or emails were also sent to a few

random RISSA members not otherwise contacted including 2 retired but active

RISSA members and the RISSA newsletter's director. The teacher authors of

the RI State Social Studies Standards Guide (a guide to resources, not a curriculum

guide as found in other states) also received notices. Tara Tetrault contacted by email an additional teacher at a private

school.

Email notices were also sent to the SAA Archaeology and Public Education (A&PE)

electronic newsletter for the Fall and Winter issues.

In response, one

What Went Right? What Went Wrong? What Can

We Take Forward?:

The Results of the PEIC K-12 Social Studies

Education Event

Were the goals proposed

for in the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education event achieved? The two goals

aimed for in undertaking this event (as described above) were (1) testing

a strategy for effectively contacting an audience of teachers and (2) targeting

the publicly-directed SHA membership with information about ‘education needs’

as opposed to archaeology needs. Examining whether or not these goals were

successfully addressed requires in part evaluating the proposed objectives implemented to achieve them.

These stated objectives (the strategies taken to reach the set goals) were

(a) creating a joint teacher/membership format for the event and (b) implementing

specific scheduling tactics.

An evaluation of success

or failure for these objectives depends on the measures employed for assessing them:

Different measures might be ‘useful’ or ‘not as useful’ (strong or weak) depending

upon which variables are considered

relevant. Multiple variables came into play during the PEIC K-12 Social Studies

Education Event -- some of which could be controlled for and some of which

were beyond our control.

What follows here is a discussion of possible measures that could be

used to evaluate the objectives designed to meet the event’s goals. This discussion

is followed by a summary of known and unknown variables that either do or

could condition the conclusions based on these measures. The result is a set

of qualitative and quantitative assumptions that can be made about the event.

From these we get an indication of what we do and do not know as a result

of the event, and what we can and can not take forward as experience from

this event.

Measures

One measure often used in assessing public archaeology events is based

on audience numbers. The ‘scheduling

objective’ proposed as a way to meet the aims for this event bears on any

assessment based on audience numbers. The event timing was designed to bridge

the professional conference and the public session. Scheduling the event as

the first offering during the Public Session meant that the membership would

hopefully still be in attendance and those members interested in public outreach

would be able and more likely to attend. This scheduling objective relates

to the goal of targeting the publicly-directed SHA membership with information

about ‘education needs. At the same time, it also relates to the teacher targeting

strategy: By attending the PEIC Social Studies education event early in the

afternoon (and learning something about ‘how to use archaeology in the classroom’),

any teachers in attendance would also be better prepared to take advantage

of the other public session offerings scheduled later in the afternoon. This

early scheduling would also maximize opportunities for teachers who might

have families in tow: kids and spouses could be expected to sit through an

early afternoon offering addressed to adults/teachers if hands-on general

activities were to follow. A critical application of the audience numbers

should take into account this objective of ‘strategic scheduling’.

Another measure that could be used to assess the overall success or

failure of the event could be based on information gained through audience surveys. Chambers (2002) has

negatively evaluated the use of surveys for this purpose in public archaeology

to date saying (repeating from his quote above):

the evaluation of archaeological public

education activities is often limited (if it occurs at all) to relatively

simple surveys designed to collect visitor demographics and gauge first impressions

related to site specifics and the valuation of archaeological inquiry. That

such evaluative efforts are often associated with attempts to justify or seek

additional support for archaeological work makes their scientific usefulness

suspect….

Chambers is correct that

surveys require critical rationale behind their implementation. It is also

true that this is something that archaeologists generally aren’t skilled in

doing. Knowing of past problems with survey results in public archaeology,

the PEIC event survey was thought about in earnest and an effort was made

to construct it so that it piggy-backed on the general public session survey

(as opposed to replicating it)[19]

and followed through on the two goals aimed for in the event. (A copy of the

survey is included in Appendix A).

The PEIC Education Event survey agenda mirrored the two-fold purpose

(two-directional aim) of the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education event in that

the questions directed at the educators in attendance were ALSO a message

directed AT the membership. The survey contained education-specific questions

adapted from professional education evaluation questionnaires. In soliciting

education specific information from teachers for future PEIC K-12 needs, the

survey also demonstrated ‘in black and white’ to the archaeologists in the

audience the type of needs educators have. In other words, the questions focused

on education needs as opposed to those pursued in many public archaeology

efforts, including that of the joint-archaeological society commissioned Harris

Poll Survey (Ramos and Duganne-Harris Interactive,

Inc., 2000), which explore public perceptions and attitudes about archaeology

(i.e., archaeology’s needs).[20]

The efficacy of this strategy for reaching these specific two aims should

be included in any evaluation using survey results.

Another measure useful for assessment

of such events is post-event feedback.

Both formal and informal feedback were sought after

this event. Feedback was gathered via the PEIC survey form, from interviews

conducted with public session participants who spent time with visitors in

the demonstration room, and from corridor talk with colleagues after the event.

This type of assessment information can be invaluable even if it remains open

to criticism as anecdotal and/or subjective. Any analysis of the gathered

feedback should include its contribution to evaluating the specifically stated

aims of the event.

Data and Results

Audience Numbers

Basic audience demographic information was compiled during the event

(See Figure 1.) From these statistics we know that there were 40 people present

at the start and 30 people (average) at the end of the PEIC K-12 contribution

to the SHA Public Session. We know that

this audience size is similar in size to that found for many papers presented

during the SHA conference meeting in Providence and it is comparable in size to last year’s PEIC

K-12 Panel Discussion with educators and archaeologists held during the conference itself (an audience

comprised of only archaeologists).

This audience size was much

smaller than that present at last year’s public session lectures offered in

ATTENDANCE

AT THE PEIC K-12 SOCIAL STUDIES EDUCATION EVENT

__________________________________________________________________

Event Schedule

Audience Totals

Male/Female ratio

_________________________________________________________________________________

Introductory Comments at the

start and

the

finish (10 minutes later):

40/37 16M

24F (at start)

Archaeology Presentation at

the start

and

10 minutes later :

47/36 19M

28F (at start)

Education Segment

taken at 10 minute intervals

30-29-30-31-29 10M 20F (at start)

___________________________________________________________________________________

Figure 1.

Audience Statistics (Compiled on-site in real time by Co-Organizer Tara Tetrault)

We know

that the audience at the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education event ‘appeared

small’ (low in turn out) to some archaeologists at the time, and that this

appearance was taken by some to be an indicator of low success for the event

(feedback comments in corridor talk). We know that this ‘appearance’ was in

part inevitable because the event was held in the hotel’s large ballroom with

seating arranged for 200 people. Had the originally assigned, much smaller-sized

room been used (Providence II/III, which have conference seating for 28 persons

each, respectively), the venue would have ‘appeared’ more full and might have,

based on this kind of ‘appearance-based’ measure, conveyed an indication of

success. However, the smaller original venue could just as likely have appeared

too small with the result being that the event would be assessed by segments

of the audience as poorly planned.

Another number-based indicator related to audience size comes via the

handouts made available for the audience.

Fifty sets of handouts were provided for the audience (left out on

chairs in the room with three sets of handouts per row on average).[21]

We collected back 26 sets of handouts after the event, meaning that 24 sets

were taken away by audience members. We do not know who in the audience took

advantage of the opportunity to have these resources.

The general Public Session Survey and the PEIC K-12 Social Studies

Education Event Survey provide minimal ‘number-based’, information with 12

and 3 survey respondents (respectively) indicating

they attended the PEIC K-12 Event. It is possible the respondents completing

these two surveys overlap. Additional information about these surveys is found

below.

Audience Composition

A measure of audience composition

can perhaps be more useful in effectively addressing the goals of, and the

objectives operationalized for, the event. The event’s

goals targeted both teachers and SHA members with different strategies (objectives)

implemented for helping achieve the desired goals for the two different audiences.

Based on visual identification by the co-organizers and feedback from audience

members, SHA members seem to have comprised a significant portion of the PEIC

K-12 Social Studies Event audience. This is noteworthy because the PEIC event

took place after the SHA conference ended. One objective involved scheduling

the event early in the public session so that SHA members might be likely

to attend (to hear the ‘education needs’ message). On this account, the visual

assessment information indicates that the audience targeted for the ‘education’s

needs’ message (the archaeology half of the Event’s audience) was present

in the room. This indicates that the scheduling and joint format objectives

(vis-à-vis the membership part of the audience) were likely successfully met.

But this does not indicate that the goal for that portion

of the audience was successfully reached: Having archaeologists in attendance

does not mean that the ‘education needs’ message was ‘conveyed’ to this audience.

In terms of the other targeted audience of invited Social Studies Educators,

we had no way of knowing how many teachers would respond to the pre-circulated

invitation fliers -- and IMPORTANTLY we had no idea of what ‘a good response

rate’ would even be because there is so little evaluation done in other events

to allow comparison with. The best we could do was ‘try and go from there’

(go forward with what we learn). Qualitative and quantitative

information

gathered from post-event interviews is useful in evaluating this teacher targeting

strategy, adding information about the audience composition. This interview

data follows below.

Data from Interviews

Post-Event

interviews were conducted with archaeologists demonstrating/presenting

in the Public Session exhibit room operating alongside and after the PEIC

K-12 Social Studies Event. These interviews took place between the hours of

3 and

At least 7

high school student visitors to the exhibit room were identified by exhibit

room demonstrators/presenters during interviews. These are students who directly stated to AIE, Thinking

Strategies, and SAA personnel that they “were directed to the public session

event by their teachers” (personal communication from SAA collaborated

by Thinking Strings and AIE). We also now know from the debrief interviews

- and from information that these presenters collected for their own needs

(see below) - that three high school teachers visited the public

session exhibit room, all of whom are identifiable as teachers of history/social

studies. These three individuals directly identified themselves ‘as teachers’

to the exhibit room demonstrators/presenters in conversation and did so again

in leaving their name and details in requesting AIE materials. One

of these teachers mentioned that his students were present as well (AIE

and Thinking Strings, LCC

personal communication).

Two of these

teacher’s names have been located in cross-referencing the AIE request list

for materials (see below) with the PEIC Social Studies outreach teacher contact

list. In other words, these teachers directly received PEIC K-12 invitation

fliers. The name of the third identified 'teacher' was not located on the

PEIC K-12 social studies teacher contact list but IS at a school whose social

studies teachers received fliers

(possibly explaining her presence as a result of ‘word of mouth’ about the

flier or as a second hand receiver of the flier [possibly posted at the school’s

teacher’s lounge]). AIE’s demonstrator thought this

teacher came with one of the identified (above mentioned), directly targeted,

teachers (AIE, personal communication). However, the AIE lesson material request

form (see below) signed by these two individuals (sequential entries on adjacent

lines) indicates the third individual is from a different school: This third

‘teacher’ writes “---school district” under the category entry for ‘organization’.

In conversation with AIE personnel, this third individual indicated her subject

was social studies education. A post-event internet search showed that her

name was not located on the department list for teachers at the school she

indicates. It is possible that this is a student teacher.

Pinning down how this third suspected

educator and the other identified teachers came to be present at the public

session is clarified by the information gathered in the general survey form (see below).

This form asked directly ‘Who did you come with today? friends, colleagues, or family - and also queries the

person’s source of knowledge about the event (How did you hear about this

flier, newspaper, Internet, etc).

The

PEIC K-12 is indebted to Archaeology in Education, Ltd., who shared

additional information they collected from the public during the Public Session.

AIE compiled a list of names from the members of the public who requested

AIE’s sample lesson plans. AIE’s

request form asked the following information: Name, Organization, Grade Level Interest, Phone

and email. Because the public attending

the exhibit room did not give me this information (but rather gave it to AIE,

Ltd. for an intended purpose) it would not be proper to collect the phone

and email details of these public session attendees. I did not collect this

information. (Note: I already have all

Below is the information gathered

by Archaeology in Education, Ltd., about the public session exhibit

room visitors. The first line in each entry is from AIE’s list. The second line is information based on cross-referencing

these names with the Rhode Island Social Studies Association (RISSA) list,

the SHA membership list, the local high school social studies teachers contact

list compiled for the invitation fliers, and, in one case, post-event Internet

research:

__________________________________________________________________

Name

Organization

Grade Level Interest

________________________________________________________________________________________

(Name removed) (Name removed: Archaeology Outreach Program) Primary

(SHA member attending the public session.

An archaeology public education focus is indicated by the affiliation.)

(Name removed) (Name removed: University)

(SHA member attending public session. Individual mentioned to AIE that she was incorporating

public education into the undergrad and grad classes that she is teaching

at her

Maureen Malloy SAA

K-12 Amer. Arch.

(Maureen is Society for American Archaeology Manager of

Education and Information. She contributed to the PEIC event (brochures) and

Exhibited in the public session exhibit room.

(Name removed) Local

(If

I remember right, Alan Leveled targeted the local Historical Societies and

this could be one of these contacts.)

(Name reoved)

(This is one of the Social Studies teachers directly targeted

by a PEIC flier (the flier carried an endorsement of the Rhode Island Social

Studies Association). Several presenters in the exhibit room noted that this

teacher attended with her husband and child [she also looked in on the PEIC

event]. She mentioned in conversation with Candice Byrd of AIE that she taught

history.)

(Name removed) Local

RI

(Teachers at this teacher's school were targeted by the

PEIC. The individual's Sir name correlates with that of other teachers and

administrators on the PEIC social studies teacher target list but not the

first name. This name is not listed at the school either (I re-checked). AIE

demonstrator Candace Byrd learned in conversation with this individual that

she was interested in social studies (see below). MAYBE this is a student

teacher? We can ask AIE to follow this up and let us know if this is deemed

appropriate and relevant.)

(SHA member who has run an elaborate, very successful,

archaeology education program with school kids

(*Possible new SHA member? Presenter in exhibit room.)

(Name deleted) (wrote down

what

(This was one of the teachers directly targeted by the

PEIC outreach fliers. He was not a member of the Rhode Island Social Studies

Association. Candace Byrd of AIE learned of his college studies in conversation

with him (where he may have come across archaeology and education in his training.)

(Name

deleted) Americorps

(This individual was in a workshop I attended earlier where

I passed out the flier. She said then that she was at SHA because she works

for an organization where there is an archaeology component (in a forest project).

*She could possibly be a new SHA member as well?)

(Name deleted)

(This individual is an SHA member who is listed with an

address at a College of Education. A search for by me on the Internet revealed

that the main web page has tabs that take one to his state Association

of Computer Using Educators and to a statewide architectural heritage

education curriculum (its goal is stated: to provide the state's children

with a sense of appreciation, pride, and stewardship for Louisiana's historic

buildings).

(Name deleted) Nearby

State Arch. Society

(*Maybe a new SHA member, however

Alan Leviellee did target local archaeology societies

which could explain her attendance.)

(Name deleted) ( a web site was listed under organization) elementary

K-5.

(I

couldn’t find out anything about this individual. *Maybe he is a new SHA member.

Maybe he is someone from the public. Maybe a teacher.

We can ask AIE to follow this up if deemed appropriate and relevant.)

* These names are not on the SHA membership

list in the 2002 SHA NEWSLETTER list but could be new members

as of 2003 and the meeting registration.

_____________________________________________________

Summary of Targeted Educator and Educator-Related Audience

Obtained from the Interview Information

From the interviews

conducted with exhibit room presenters and the AIE list we know the following

about the audience composition at the Public Session in toto:

Thanks to the observations of Maureen Malloy of SAA and Jana

Steenhuyse and Heidi Katz of Thinking Strings LLC, and,

in particular, the exceptional observation skills of AIE, Ltd.,

partner Candice Byrd, (all presenters/demonstrators in the exhibit room) we

know that there were two small groups of students who attended the SHA Public

Session:

Thinking Strings personnel

said they observed what they thought were “two groups of students” -- one

had “3 demur girls who could possibly be from a private Catholic school” and

one group was “four punky-looking and pierced kids”. (Note: one of the Thinking

Strings demonstrators is an ex-teacher). Candice Byrd learned that the

group with 3 female students represented 12th graders. A teacher

that came by separately pointed out his students to the Thinking Strings

presenters. Candice Byrd of AIE noted as well that there was “a teacher who

brought along students”.

We additionally

know that these students attended the event as a way to earn school credit:

Heidi Katz learned that one of these groups of students

attended the public session because they “would get an A on a quiz for being

here”. The teacher (male) who pointed out his students told Candace Byrd that

“he didn’t like to give extra credit but he was doing so in this case because

the kids were coming in on their day off” (note: the weekend, let alone the

Martin Luther Kind holiday weekend, is a variable affecting turn out). Jana

Steenhuyse learned that this same group was thinking

of “going over to the ice skating rink across the street if they were done

[with the public session]” (note: competition for the event).

We

know that three teachers of social studies were present at the Public Session,

two of whom are known by cross-listing the names to have been targeted by

the PEIC outreach strategy. One of these is the teacher who encouraged his

students to attend for credit. Candice Byrd learned that one of the teacher's

(J. Cassidy) had gone to college at Washington and Lee so it is possible that

he may have had exposure to archaeology in education courses taught there.

Candice learned in conversation with Tina Silva (whom Candice took to be a

teacher) that Tina taught social studies. This is the teacher whose name was

not on the contact list but who mentions a school where teachers were targeted

in her details on the AIE list. We also know from the AIE

list that archaeologists with a research or employment focus in public archaeology

took advantage of the opportunity of the SHA public session to learn about

and from their colleagues active in public archaeology (providing some insight

into what is a current SHA membership interest and need).

The interview data indicates that the teacher targeting strategy brought

several teachers and in one case, a teacher’s students, to the Public Session

- although not specifically to the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Education Event.

Data From the

General Public Session Survey Form

Additional information

about the targeted educator audience outcome and the Event audience composition

comes from the general Public Session Survey Form. The PEIC designed a general

survey form for the Public Session separate from the PEIC K-12 Social Studies

Education Event survey form.[22]

Announcements about this survey with a request that the public complete them

were made by the Public Session Organizer several times between

Four of the

30 visitors who completed the general ‘Public Session Survey listed their

occupation as educators.

Two of these attended the PEIC K-12 Event, one with students in tow:

#1 writes ‘Social Studies

Teacher – High School’ under ‘occupation’. This individual lists their education

level as ‘MA’, replies ‘self’ in regard the number in the party, and checks

the female age category 26-35. They report they heard about the event by ‘mailing’

which indicates they received or had access to the pre-circulated PEIC K-12

Education Event flier.

#2 writes ‘Educator’ for

occupation, writes “Teacher from Portsmouth High School” in the right margin,

lists MA (level of education), and has “my class” written next to the ‘I am

here today with family, friend or colleagues’ question. The choice ‘5 or more’

is circled for ‘number in party’ and the ages 14-19 are circled for both male

and female categories (no age or sex however appears recorded for the teacher).

This individual indicates that they heard about the event by ‘mailing’ which

indicates they received or had access to one of the PEIC K-12 fliers sent

to teachers. The responding teacher indicates attendance at the PEIC Event.

#3 writes ‘Teacher’ for

occupation, lists MA under education level, reports two in the party and ‘present

with family’. The 14-19 year old female age category is circled as is the

26-35 year old male category (party of 2). This latter is the teacher presumably

accompanied by a child or younger sibling perhaps). This teacher records they

heard about the event by word of mouth. They may not be a Social Studies teacher.

They attended the PEIC Event

#4 writes ‘Social Studies

Teacher’ for occupation, BA degree is written in (modifying AA option), this

individual attended with a ‘family’ of more than 5 (note: only the ‘or more’

portion of the option is circled, not the ‘5’ in ‘5 or more’). The female

age group 36-46 is circled and the male age groups circled are ‘8-13’, ’14-19’

and ’36-46’. This individual records hearing about the public session from

the SHA Conference Program.

Three other general Public Survey forms were completed by respondents

that indicate they (sometimes with a companion/family members) attended the

PEIC K-12 event amounting to a total of 5 people. Some of these individuals

may be family in attendance with their teacher spouses. Others may have come

as a result of SHA membership-related advertising for the education event.

It is also possible that some of these visitors are members of the public

who came to the general Public Session and saw the PEIC K-12 event as well

just by chance.

Form #5 identifies his

occupation as ‘Counsel (Marine)’ with MA for education level and also puts

under ‘Other’(education) “LL.M., BCC”. He is a 61-70

year old male (age/sex category circled) who was by himself. He attended the

PEIC Education Event and the exhibit room. He records that he heard about

the public session in the SHA Conference Program.

Form #6 records a family

group of 3 (circled) with two 47-60 year olds with a younger family member.

Both male and female age categories are circled (for the 47-60 year old

age group) as is the 14-19 year old male age group. The recorder lists under

occupation ‘Attorney’ with ‘JD’ as the education level (under ‘Other’). This individual circled ‘word of mouth’ for how they

heard about the event. This group visited the Exhibit room and attended the

PEIC event. The Exhibit Room option was checked as the event that ‘struck

you as most interesting’ and the Education event was checked for ‘not holding

the child’s attention’.

#7 is a female age 26-35

attending on her own, with an ‘AA’ degree, with the occupation listed as ‘child

care’. She attended all three offerings of the public session and checked

the Speaker’ Forum as most interesting. She heard about the event at the library

(filling in the ‘other’ option line for ‘How did you hear about this meeting?’).

Seven other forms have respondents that identify themselves as students

either by circling ‘high school’ under grade level and/or filling in ‘student’

under occupation and are presumed to be in attendance at the Public Session,

although not the PEIC event alone, as a result of flier outreach to local

Rhode Island teachers:

Three survey forms (#8,

#9, and #10) are nearly identically filled out. All indicate ‘3 in the party’

and indicate attendance in the Exhibit Room and the Teacher’s Program. These

three record ‘word of mouth’ as the source for information about the event

although one of the respondents writes in the ‘other’ line option “teacher”.

All three are females with the age group 14-19 checked off and ‘friends’ checked

off. All three of these indicate the Exhibit Room as most interesting and

the Teacher’s Program as least interesting.

A fourth high school student

(survey #11) also indicates attendance at all three events indicating the

Exhibit room as most interesting and the Teacher’s program as least interesting.

This respondent is a male, 14-19 years old in attendance in a ‘party of 2’

(the other marked as ‘colleague’). He records that he learned about the event

by ‘word of mouth’. It is impossible to match up this individual with another

record to find the other of the 2 in his group.

Two other high school

students (survey forms #12, #13) record ‘2’ as the number in the party of

‘friends’. These two forms have identical responses for the check off options

and circle options so it might be assumed these two came together. They say

they heard about the event from ‘teacher’. Both indicate attendance at the

Exhibit Room and the Speaker’s Forum, finding the former most interesting

and the later the least interesting.

Another survey form (#14) is marked with ‘student’ under

occupation and also has high school circled but 2 are indicated as the number

of people in the party which is listed as ‘family’. The female 14-19 age category

and the male 20-25 age category are circled. The events attended include the

Exhibit room and the Speaker’s Forum (the former marked as most interesting).

This respondent circles ‘the internet’ as the source of learning about the

event. It is possible that a younger sibling filled this out for the party

of two. This internet source for hearing about the public session could be

the A&PE notice for the PEIC K-12 event (which also listed all the Public

Session events). One member of the public did email the contact number for

the PEIC event organizers included on the A&PE notice.

George Brauer, the Social Studies Curriculum

Specialist who advised the PEIC K-12 on the back up model for the Event discussion

[should the teachers not want to discuss]) expected that we would get few

or no teachers in attendance. He thought this a) because social studies is

unorganized in RI and we couldn't use the social studies instructional networks,

and b) because of the holiday weekend conflict. He has recently said that

the fact that we got as many as we did is "a good success" rate. (He said

this to a third person -- I have not talked to him directly yet.) Thinking

as a curriculum specialist who operates through such networks for sharing

information widely, and knowing that teachers like their holidays, he thought

no one would show. So while this is a singular and subjective measure, our

advising educator for the PEIC K-12 event saw the targeting strategy as a

surprise success with this turn out.

Email correspondence should also be considered in this enumeration

effort. The email notice and hard

copy flier pre-circulated to the

In

addition to these teacher targeting goal results, at least one other social

studies teacher (a new member of SHA) was present at the public session in

the PEIC event as a result of a member-directed flier (Jim

McDevitt who is also a new SHA member). This person

received the flier at a workshop held the day prior to the conference and

was personally encouraged to attend.

Two additional individuals in the PEIC K-12 event audience are suspected

[by Tara Tetrault, Linda Derry, and myself] to have

likely been educators. These middle aged males were not recognizable to any

of us and they responded visibly to some of what was said in the PIEC event

introduction and during the modeling of the

Taking into account the 5th

identified teacher (the new SHA member) in attendance at the PEIC Event or

at the Public Session as a result of a PEIC Event Flier, we can surmise the

following in a preliminary assessment of the *possible* ‘contact/impact’ as

a result of this episode of targeted outreach *in

general*. (This would not relate to the PEIC K-12 Social Studies Event

alone [the results for which can be found below] but rather to the Public

Session as a whole]). Using the MNI for identified social studies teachers

present at the Public Session in general (the PEIC K-12 Event, the Panel,

and the exhibit room), and knowing that each teacher teaches on average 4

classes of students (with a low average classroom size estimation of 28 students),

the following is the resulting *ideal possible* ‘contact/impact’ rate:

5 teachers (MNI) x 4 classes each (with 28 students in each)

= a ‘potential’ 560 students

that 'may' learn something involving

archaeology as a result